I first was introduced to Ukrainian-Canadian artist William Kurelek in 2012, when the extended version of the original documentary William Kurelek’s The Maze (7) was screened in a church near my house as part of the “Rendez-vous with Madness Film Festival.” The original 1970 film was based on 1953 psychiatric art that William Kurelek had painted while a patient in Maudsley Hospital, London. This bleak self-portrait that revealed “the darker side of human nature” (1) led me to explore his later work in the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) when I happened to be there as a performer in a sound poetry group.

William Kurelek's The Maze - Official Trailer from Nick Young on Vimeo.

"The Maze is a painting of the inside of my skull", William Kurelek

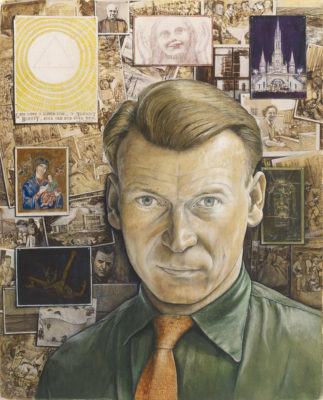

I remember studying a large tableau of Kurelek’s entitled “Don Valley on a Grey Day” (1972) and “Self-Portrait” (1957) which showed a shift from the “portals to his suffering” (4) of his asylum days to his “new post-conversion path” (4). This painting, which glared back at me in AGO’s Thomson Collection (6), shows “a confident and optimistic self” with “narratives [which] are more orderly rather than free-flowing, painted as photographs and postcards neatly stacked to a bulletin board.” (4)

I remember studying a large tableau of Kurelek’s entitled “Don Valley on a Grey Day” (1972) and “Self-Portrait” (1957) which showed a shift from the “portals to his suffering” (4) of his asylum days to his “new post-conversion path” (4). This painting, which glared back at me in AGO’s Thomson Collection (6), shows “a confident and optimistic self” with “narratives [which] are more orderly rather than free-flowing, painted as photographs and postcards neatly stacked to a bulletin board.” (4)

I recall being fascinated by the way Kurelek would sign his name in the bottom right corner of his artwork. It looked to me like the etchings on an asylum wall. I later learned that “when urged by [his employer and art dealer Avrom] Isaacs to provide signatures on his work, Kurelek did so with a cross above his initials to indicate that his art was strictly at the service of God.” (4)

Youth and "Devouring monsters"

A child during the Great Depression, William Kurelek’s family moved from Alberta to a new farm in Manitoba. William recalls having trouble with “hallucinations” and “visions of devouring monsters” as a young boy (5). He also had a strained relationship with his father and was bullied by older boys at school (3). Perhaps William’s intense work ethic came from his parents’ farm in Manitoba where he had “to get up at 6 am to fetch the cows for milking” (3). Known to be the “dreamer” (5) among his numerous brothers and sisters, William regretted never being able to please his father. Scorned for his lack of athleticism and mechanical aptitude (5), William found some confidence at a young age through his ability to draw (3). While feeling isolated and confused about his identity, a young William Kurelek found himself working at a lumberjack camp in the bush in 1947, where he sought “peace of mind and strength of body” (5).

In 1949, William graduated from University of Manitoba with a Bachelor of Arts (Latin, English, History Major) (2). Instead of following the path his father envisioned for him, William was set on becoming an artist and enrolled at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, where his studies were curtailed by a decision to move to England in 1952. While in England, William’s “mental health deteriorated” (1) to a point where he felt inclined to commit himself to psychiatric care.

Now he's committed

As a patient in Maudsley Hospital, William “described his problem as depression and depersonalization. He was at this time an extremely introverted, isolated personality, obsessed with his own problems and almost incapable of relating to others.” (5) “In the small high-ceilinged room that served as bedroom and studio, its tall, narrow window overlooking the lawns and trees behind Maudsley, Bill began work on […] strangely diverse pieces.” (5) “In October 1953, Dr. Davies wrote to the senior physician of Netherne, requesting admission on a long-term basis for a highly talented artist. […] Bill was described as having a schizoid or introverted personality.” (5)

While at Netherne, Bill’s depression spiraled into a suicide attempt. “Bill’s gesture, on August 11, 1954, involved eight sleeping tablets, a new razor blade, and two months of planning.” (5) “He was found in a cupboard. His stomach was pumped, and his numerous shallow cuts were cleaned, he woke up in a locked ward.” (5) “I Spit on Life (c 1953-1954) painted not long before he attempted suicide in 1954, is quite possibly Kurelek’s bleakest analysis of how his past had affected him”. (4)

According to Edward Adamson, a British art therapy pioneer and staff member at Netherne, “it was through paint that William found his own way back to health.” (4) “Later that year, Kurelek […] underwent a series of 14 electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) sessions” (4). “Electro-shock”, was (and still is to this day) deemed to be beneficial for patients suffering from severe depression. “In the fifties, Netherne averaged one hundred treatments per week.” (5) “In clinical observation, ECT reduced short-term memory, usually leaving long-term memory untouched.” (5) “The first treatment, unmodified [by the muscle relaxant scoline], sprained [William’s] back” (5)

In 1955, William Kurelek was discharged from Netherne (2). This “outsider” (2) and “non-conformist” (4), with a hazy memory from his multiple shock treatments, was more determined than ever to pursue art as a career path and promptly found work as a framer and “trompe-l’oeil” (fool-the-eye) still life artist in the British art scene (5).

Eschatological & prolific work

In February of 1957, William Kurelek would formally join the Roman Catholic Church (5). This conversion gave him the faith to carry on. (1) His later work was often “eschatological” (4), in other words, forecasting apocalypse or planetary doom, and definitely shifted toward themes of “greater moral and religious meaning” (2). His religious search had begun while at Maudsley, where he met a motherly therapist who had battled her own depression with faith. (3) “Whatever it provided to him spiritually, Kurelek’s conversion connected him to a very different religious tradition than that of his [Ukrainian peasant] ancestors.” (4)

In 1959, Kurelek would take his newfound faith and framing experience back to Toronto. He had studied the style of master painters Pieter Brueghel, Hieronymus Bosch, Van Gogh while a mental patient in Europe. In June of that year, he took a sea vessel called the Ivernia back to his homeland. (5) When he arrived in Toronto, William “registered for teacher training at the Ontario College of Education. He was devastated to be rejected on the fourth day as psychologically unfit for the profession.” (5) However, he was given opportunity to work as a framer at The Isaacs Gallery in Toronto with his extensive framing experience garnered abroad and his keen and detailed “trompe-l’oeil” artist skillset. “In a closet under the stairwell [in the Isaacs Gallery workshop] Bill kept a bedroll and would take a nap in the middle of the night when he was framing or painting.” (4)

In 1960, Kurelek would have his first of many art shows at The Isaacs Gallery. “[His] first exhibition with Isaacs […] consisted of some twenty paintings” including his 1957 self-portrait. (5) “The first Kurelek exhibition drew the biggest crowd the four-year-old gallery had ever had.” (5) “Prices ranged from $160 to $500, and paintings sold briskly”. (5) “The artist enjoyed framing. He usually framed his own work, often in colourful Ukrainian designs and old barnwood. He would continue to frame for Isaacs until 1970, and to use Isaacs’ facilities for framing his paintings, keeping track of the materials used and reimbursing his dealer.” (5)

In 1962, William Kurelek met Jean Andrews in Toronto and they married shortly after that same year in the “Church of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, at Mt. Pleasant and St. Clair Avenue.” (5) “A week’s honeymoon was spent in Quebec City, Montreal, and New York, much of it in art galleries.” (5) “Jean was open and calm as he was shy and intense […] she would give him the help he needed when his depression threatened to return.” (3) The couple would have four children.

In 1965, the Kureleks would move to the Beaches. (5) “Bill lived in the middle of one of Canada’s largest cities, yet remained rural by attitude and inclination. His East-end neighborhood bordered on Lake Ontario. A ten-minute walk would bring him to the beach, and a shorter one to a deeply wooded ravine.” (5) “Working in a very small studio in the basement of his Balsam Avenue home in Toronto, he painted on a flat table surface, never an easel.” (4) “The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 led to a rash of private [bomb] shelters in the Toronto area […]” (5)

This Cold War paranoia affected William deeply, to a point where he became obsessed with building a bomb shelter (with amenities) in the small basement of their home. “From the late sixties on, Isaacs frequently expressed his concern that Bill was painting too quickly […] Bill continued to work fifteen and eighteen-hour days”. (5) In 1969, William Kurelek was invited to a Cornell University seminar to speak about mental illness. (2) “[William] was [also] invited everywhere as museums across Canada, the United States, and England showed his work.” (3)

Neither weak nor lazy

“Perhaps his most marked quality: extraordinary self-discipline. Often cloistering himself away for days at a time to complete a series, Kurelek thrived under the constraints of time and space, working all hours of the day and night, and often fasting for the duration in hermetic isolation.” (4) “Henry Slaby, Kurelek’s accountant in the 1970s, asked the artist why he worked so hard: ‘He said he felt an inner urge-something pushed him to produce, and he felt fulfillment in it.’” (5)

“Through Dr. James Maas [of Cornell University], Bill would participate in an award-winning documentary film on his life, and the publication of his autobiography. […] Maas made it possible for him to comment on his slides to an audience of some twelve thousand students in a university concert hall.” (5) “Bill’s research methods […] were heavily dependent on photography. Something between one-third and one-half of the Council’s grant of nearly five thousand dollars went into cameras, film, and the cost of filming his drawings. He carried two relatively sophisticated cameras and sometimes advanced using both at once, like a Western gunslinger.” (5) “He photographed from the windows of hotel rooms, and from taxis and speeding trains.” (5)

In 1976, one year before dying of cancer, Bill received the Order of Canada. He had made more than 2000 paintings in just 25 years. (4) Bill reconciled with his father while dying in the hospital and “wanted to show him photographs he’d taken of his Ukrainian trip.” (3) “His editor, Mary Cutler of Tundra Books in Montreal, said of him: […] ‘He liked to paint in series, and he would retreat to a hotel room or to his farm for 10 days at a time, attend mass, each morning have a cup of coffee, chew wax and paint for as long as seventeen hours a day.’” (1)

Maze

While Kurelek’s 1953 painting “The Maze” was what first got me interested in the man, I found it particularly compelling that the white rat stuck in a compartment at the center of a bleak psychiatric mind-maze, was able to navigate out and lead a fulfilling life, while leaving a significant mark in the Toronto art scene, to a point where psychiatric patients, like myself, can enjoy his “Self-Portrait” (1957) on an outing to the AGO or be inspired by his eccentric genius when they stop in and browse material at their local library branch.

Written by Toshio U-P

Works Cited

1) “William Kurelek-Painter•illustrator•author”, Canada House Gallery, Trafalgar Square London, 11 January to 8 February 1978, An exhibition organized by the High Commission London in collaboration with the Isaacs Gallery, Toronto and William Collins Publishers, London, Catalogue published 1978, Printed by Merlin Colour Printers Limited.

2) Website: William Kurelek ǀ The Messenger

Address: kurelek.ca/biography

3) “Breaking Free-The story of William Kurelek”, May Ebbitt Cutler with Art by William Kurelek, Tundra Books, Toronto, 2002, p.12, p.16, p.20, p.30

4) “William Kurelek ǀ The Messenger”, Essays by Tobu bruce [et al.], Library and Archives Canada, Catalogue of an exhibitionheld at Winnipeg gallery, Art Gallery of Hamilton and Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 2011-2012. p.106, p.50, p.52, p.48, p.49, p.56, p.104, p.180, p.136, p.138, p.13

5) “Kurelek-A Biography”, Patricia Morley, Macmillan of Canada, Toronto, 1986, p.21, 18, p.52, p.4, p.88, p.92, p.101-102, p.103, p.85, p.109-110, p.116, p.145, p.148, p.155, p.156, p.158, p.171, p.174, p.202, p.175, p.233, p.304, p.236, p.242

6) SELF-PORTRAIT (1957)

[William Kurelek]

1957

watercolour, gouache and ink on paper

47.5 x 38.0 cm

The Thomson Collection, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

7) THE MAZE (1953)

[William Kurelek]

1957

91 x 121 cm

Bethlem Royal Hospital, London

8) William Kurelek’s the Maze, Dir. Robert M. Young, Toronto Premiere (Rendezvous with Madness Film Festival), October 19, 2012.

Permalink //

Thanks for this history of William Kurelek, Toshio. I found the Maze painting totally fascinating, and this artist's ties to the Toronto art scene really intriguing. You have piqued my curiosity... Awesome piece for the Mad Times!

Permalink //

thank you Toshio for this well researched, beautifully written article about William Kurelek.

I have been drawn to his work for many years, and especially so since visiting the somewhat hidden gallery near Niagara Falls which is devoted to his work.

Your article helps me better understand the inner workings of this man.