Written by Kevin Healey

For some “mad” is an identity, for some a badge of honor, or a cap-badge worn as an act of resistance. Others would seek to define “Mad” as something more, to define it as a category of person, a group to which some people rightfully belong and others do not. For some it is, like the song: “Me, a name I call my-self,” – sometimes. For some, it’s just a word we use when no other word better fits some quality we are trying to express.

For me, if you want to tell me what I experience, what to call that, who I am and what to call myself, then I struggle to see how you are doing anything different from anyone else who would seek to do the same and impose their terminology on me. I thank you for trying to be of assistance, but I’m well able and quite happy to do that for myself.

Ken Robinson shares as a joke a line by Jeremy Bentham:

“There are two kinds of people in the world: those who like to divide the population in two,

and those who don’t.”

Me? I try to remain in the latter group.

Paolo Freire wrote about how sectarianism becomes a powerful force amongst those who are oppressed – the sects and sub-sects we divide ourselves into fight against each other and in that fight we lose focus of our shared struggle for emancipation. That we do this only aids those who continue to oppress. It is easier to divide and fight amongst ourselves than it is to hold true to common cause. We become alike with ants or rats – climbing up on each-others’ backs to the top – that we might be installed as the new oppressor in the manner of the pigs in Orwell’s Animal Farm, “All animals are equal, some animals are more equal than others.”

Desire to define terms we use and how they must be used comes — maybe — from a good place, seeks clarity, but it too easily, too often ends up sucking like a big sucky-thing. Language is not fixed and if it were then it would fail –- because the world it describes is not fixed but constantly evolving, as we too evolve and grow and too our understanding grows as we act in and engage with the world.

You and I might use the same word, but we will use that same word to mean a whole variety of things. Some of that meaning will be shared, some not. “Mad” to you is not quite the same as “mad” to me.

When we seek to impose our words on others, or when we seek to impose our preferred meaning of particular words on others – telling them how, when, and where they must, and must not use a term, whether they can use it — is that not just what those who we might criticize do to us: tell us what words to use to name ourselves? I choose not to play that game.

It is fascinating for me how the word “diagnosis” has become so important in our society – of course, the common meaning in modern discourse, as you’ll find in any dictionary is that of “medical diagnosis”, or “diagnosis as pertaining to medicine”.

Yet if we look at the etymology (the origins of the word) it means:

“To set apart from, in order to come to know. “

Having been set apart is certainly something we might experience when we are given a diagnosis: set apart from the rest of humanity, we become “the diagnosed” or confined, as Franz Fanon put it, into ‘the zone of nonbeing’, no longer being worthy to be considered as a being, or as human.

No longer seen as human, but required, or at least expected, to conform to a category or fit within the box of the diagnosis we have been given. As is so often the case when we seek to fit people into boxes, many of those we squeeze into such boxes will struggle, and as a result some will find themselves in a state we might call “mad.”

We have become so keen to diagnose ourselves, and each other that it has become a favourite pastime. So much so, that the Internet is replete with handy-dandy apps, tools, and schemes to help us do just that in a few clicks.

Maybe we don’t want to be same as “them” – and for good reasons. Maybe in resisting those identities imposed upon us we need to seek and to create our own identity. And in doing so find like-identity with others. This is a natural process and a good thing when we make our own choices. But there is also a fine line between making our own identity and imposing identities on each other and / or also excluding others from using a descriptor that they feel suits them because we decide it does not fit our idea of how to use the same term they choose for themselves.

When “mad” becomes a term that is defined by a few who occupy self-appointed positions of authority, how is that any different from any other diagnosis imposed upon us by a different few in different self-appointed positions of authority?

I believe each of us has the right to name our own experience in our own terms and to call ourselves whatever the fuck we want…

And think it would be a better world if we could make space for each other to do that…

If we lay claim to the word “mad” – if we claim authority to define how others must use “mad” then that is problematic for me.

What power relation, then, and with whom, are we exercising when we claim authority to know how the word “mad” must be used by others? If we are merely claiming power of how that word applies to us then there is no harm – but is that all?

So, if I’m suggesting it’s problematic to seek to define how others use “mad”, at least about themselves — and I am — then what might we do?

Mad is the word

If ever there was a word that defies definition then surely “mad,” and not “grease”, is “the word”.

Suspending ideas about madness

If on the one hand, seeking to define how others use a word is tricky, then, on the other, explaining what we mean when we use a term is a good thing.

In versions of practicing dialogue that I learned, doing this is part of what is sometimes called “suspending judgment”. That is not to mean — or at least only to mean — withholding, not-judging just yet, but meaning to hold-up our judgments, assumptions, and mental models that they might be seen, by all, including ourselves.

So in that spirit, here is what I mean, at least what I mean right now, today, as I write this, when I use the word “mad”. You’ll have your own meaning some might be similar.

Mad as state of being

To me “mad,” or madness, is not an identity but a state of being, or an attitude. It may also be useful to know that for me identity, too, is something that I experience as a fluid thing — not a fixed or categorical thing. For instance, I am known for my work in hearing voices, and am honored to have received the first Intervoice award for Innovation, but I do not call myself ‘voice-hearer’ any more than I call myself ‘air breather.’

I don’t really mind if you do, I just don’t. I do both these things, but I do lots of other things too.

Likewise, I don’t mind you or anyone else calling me “mad” – it is far better thing to be called than many of the things that I have been called. But, still, it is not often something I call myself.

Equally, I’m happy to use the word “mad” to describe some thing I see as having qualities of “mad” in the same way I might use any other term that comes to mind and that best fits what I’m trying to express.

Naming Rights

I believe we each have the right to name our world, name our own experience in the world and name ourselves by using words of our own choosing.

And, just as I claim that right for myself, I also believe you have the same right.

However, I’ve also learned that when it comes to the words we use to describe others it pays to be respectful and use language that does the least to categorize, pigeonhole, or box people in.

The words we choose to describe others reveal much more about ourselves than they can possibly say about another.

Mad, a name I call myself

I don’t really call myself anything, I just don’t feel a need to, but “mad” is something I could call myself.

Mad as the natural state of the universe

We don’t call it “madness” but it is essentially the same thing on the grandest possible scale: entropy is the natural state of the universe. Since the Big Bang, all energy has been dispersing at an ever-rapid rate. Even after hundreds of years of human efforts to impose order upon that, make useful gains to harness it, still: entropy rules, ok?

And there is something very odd, very moralistic, in an understanding that energy must be useful, that unless used for gainful human purpose it is wasted, when energy just is.

What is madness but the human form of entropy? The chaos, creativity, entropy, resistance, refusal to conform and comply that is judged by society as not useful; the wild and the wildness within us that we fear most?

Entropy and madness are both necessary – without some chaos nothing can change. And there is plenty in this world that needs to change so we best get used to some madness.

Madness is the beginning of a journey it’s not supposed to be the end result.

-Jeanette Winterson

Madness and illness

For me there is no mystery in why people find themselves experiencing what often gets called “mental illness” – none whatsoever.

Life can be overwhelming. People will and do get overwhelmed by life events, we can and do become disconnected from each other and we can and do become disempowered. This is not in itself an illness, though it can lead to us becoming very ill indeed: as social animals, isolation does make humans ill.

However it manifests, a person’s struggle always makes sense within sufficient context. If it doesn’t make sense to me yet then that is because I have not yet drawn the boundaries of that context sufficiently-wide to enable me to see ways in which it can make sense.

The ways we diagnose, categorize, and describe people as “ill” are largely social constructs. As an example, the list of “symptoms” of “psychosis” are things that require some judgment of societal acceptability: that line of what is acceptable/not acceptable is drawn in accordance with social attitudes, mores, and habits.

Societies have, for centuries had, ways to compartmentalize and cast to the periphery those people deemed to be “too different”.

We fear the unknown, and “madness” is the very manifestation and emergence of the unknown from within us. The acceptability (or not) of the apparent chaos within a person or surrounding a person is largely a social judgement – where the dividing line sits is determined socially. On one side of that line and you might be seen as odd, eccentric, strange, talented, a great artist; while on the other side you will be seen as too weird, too different, others will be afraid and want to contain you so they can feel comfortable again.

“Mad” as resistance, rebellion

“Mad” is sometimes used as a term to signify resistance to that crap. Especially when that crap involves a person being deemed so different that they must be “ill” then “Mad” might be a term a person might use to reclaim rights and self-determination.

Mad as right to be, right to be different, is something we might use in defiance, to resist ideas imposed on us: such as, that we struggle because of ‘illness’ or because we have some ‘biological deficit’, or ‘brain disorder’ when really it’s just that people are different, so how about you fuck off and let me be.

In that, for me “Mad“ is a way to declare “I can think and speak for myself, thank you very much.”

Certainly, that is in large part what MADx is about – co-creating spaces in which we can come together to find our voice, use our voice, witness each other and be with each other doing just that.

Likewise, for me the term “survivor” means…

I’m still here

– you fuckers!

“Mad” can also be celebratory – of what it takes to fight our way through all the layers of crap so we can find a place we are good with and good with ourselves in that space.

Mad as celebration

For me the best, most generative, most inclusive way to use the term ‘mad’ is as a defiant, celebratory, unapologetic “Mad” — as joining together in a sense of pride both individual and collective – “this is me, hear me roar!”

In the way that Ernest Becker said of reality:

“Reality is just a word and should only be used with quotation marks around it”

I often think of Mad in a similar way…

So here’s to the “mad” ones, eh?

Kevin Healey © November 2016

Kevin Healey “Mad, innit?”

References

- Grease [Video file]. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x18pVYUHJwA

- Fanon, F. (2008). Black Skin White Masks. New York: Grove Press. Translation by Richard Philcox

- Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. New York: Vintage Books.

- R. (2016). Here comes MADx …by night. Retrieved December 19, 2016, from https://the-rebellion.ca/2016/07/13/here-comes-madx-by-night/

- Bring on the learning revolution! (n.d.). Retrieved December 19, 2016, from https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_bring_on_the_revolution

- Winterson, J. (2011). Why be happy when you could be normal? Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf Canada.

Images

Original design by Kevin Healey

Photo: By Photograph by Oren Jack Turner, Princeton, N.J. Original image cleaned/leveled and cropped by User:Jaakobou. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Design Layout, misquote by Dave Umbongo

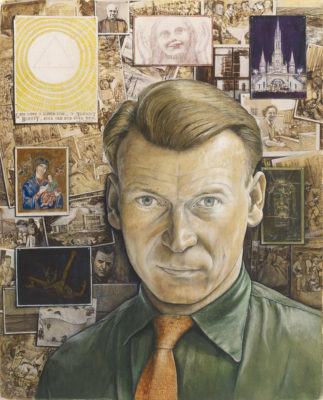

Photo: Unknown, from: http://www.nndb.com/people/323/000095038/

Layout: Dave Umbongo

I remember studying a large tableau of Kurelek’s entitled “Don Valley on a Grey Day” (1972) and “Self-Portrait” (1957) which showed a shift from the “portals to his suffering” (4) of his asylum days to his “new post-conversion path” (4). This painting, which glared back at me in AGO’s Thomson Collection (6), shows “a confident and optimistic self” with “narratives [which] are more orderly rather than free-flowing, painted as photographs and postcards neatly stacked to a bulletin board.” (4)

I remember studying a large tableau of Kurelek’s entitled “Don Valley on a Grey Day” (1972) and “Self-Portrait” (1957) which showed a shift from the “portals to his suffering” (4) of his asylum days to his “new post-conversion path” (4). This painting, which glared back at me in AGO’s Thomson Collection (6), shows “a confident and optimistic self” with “narratives [which] are more orderly rather than free-flowing, painted as photographs and postcards neatly stacked to a bulletin board.” (4)