Toshio U-P

On my way to a spoken word event in Kensington Market, I walked by the College St. site (formerly known as the Clarke Institute) and wondered how long the structure built in the 1960s would remain standing at the North end of Chinatown. Once a patient at the College and Spadina location, I remembered looking out a small window onto College St. and wondering what was wrong with my suddenly unquiet mind. Famous (or infamous) Toronto psychiatrist Dr. Charles Kirk Clarke (1857-1924), whom the mental health facility was named after, wasn’t known to me at the time. It wasn’t until a relapse five years later, on a different site, that I would learn more about the eugenics of psychosis and what made mental health facilities (like the Clarke) so scary to patients locked in during the night.

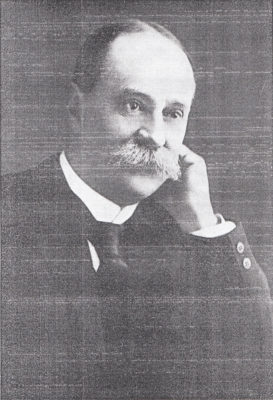

A proponent of the Canadian mental hygiene movement, C.K. Clarke founded Emil Kraepelin’s clinic in Munich, an exemplary model to replicate in Canada, and was instrumental in changing Canadian “asylums” into “Hospitals for the Insane” (1). After finding an old biography of the Canadian psychiatrist at the Toronto Reference Library (2), I was amazed that this historical figure, who was photographed here in Berlin at the turn of the century, has come to be known not based on his polished suits and characteristic mustache, but by his embodiment of one of Toronto’s most mysterious (and even sinister) landmarks.

The College St. site, which still holds confidential records of my diagnosis and mental health history, will continue to operate as a 24-hour emergency facility in the immediate future (3), despite a scare that it would be turned into condo space with a severe rent increase (4). To demolish “the Clarke,” and to erase its dark institutional history (5), would be saying that what I suffered in high school and university never happened and that those years should be forgotten like the deleted memories of shock victims after multiple rounds of ECT for their severe depression.

When mental hygiene became less fashionable, and words like “mental health” replaced it, how did Dr. Charles Kirk Clarke fit in to the history of psychiatry in our city? It is well-documented that “[w]hen Dr. Daniel Clark retired as Superintendent of the Toronto Asylum, a position he had held for thirty years, C.K. Clarke was offered the post [and] […] took up his appointment in Toronto in September 1905.” (2) Among the psychiatric patient community, however, he is occasionally associated with an institution’s “out-of-sight hellholes” where the “worst abuses happened” (5). Others outside the community may prefer to characterize him as a misunderstood and once celebrated mental health pioneer and “expert witness” who deserves recognition, having “attended more than sixty murder trials where the plea of insanity was raised as a defence” (2). The truth is, when the Clarke Institute still stands as a looming tower in the Toronto night, the debate can continue over whether this doctor’s views on immigration reveal his racial bias (5) or his professional insight on how to select new (‘non-defective’) Canadian citizens from abroad.

If Dr. Clarke represents all that is vile about psychiatry in Canada, what does this say about the institutions that once backed the doctor and now want to distance themselves from him? It would be unfair to say that the University of Toronto is a backward institution if they once had him as their Dean of Medicine. Also, maybe it’s better to say that the Canadian Mental Health Association, which was once called the “National Committee for Mental Hygiene” when Clarke co-founded it (6), has moved out of the dark storm clouds of eugenics and into the clearer skies of the mental health era.

As condo space reaches skyward across the street from the Clarke and as the familiar squalor of Chinatown starts to be replaced by modern and slick new development, the tall facility is gradually losing its visibility from the south, making me wonder still how long before all of the mental health hardships, crises and backward history associated with the site suddenly vanishes completely from our city’s guilty conscience.

As the built landscape in the Chinatown area modernizes and as the Ontario mental health sector changes its treatment and containment methods in urban centres, the Clarke is at risk of being demolished under the pretext of being too out-dated and not state-of-the-art like it once was. Along with the Clarke’s demolition, however, poorly managed mental health cases, back ward histories, and cases of neglect and displacement would be erased from the province and city’s record in such a way that patients would not be credited for their hardships and a very important gap would exist in our Toronto Mad community’s history. It is important for c/s/x/m (consumer/survivor/ex-patient/mad) community members to share their stories about the Clarke (or College St. site), as history needs to be told from our perspective while the building still stands.