Ariane Bakhtiar

Note to the Reader: Terms like mad, crazy, drunk, or junkie are often harmful in that they have historically been used to marginalize people with mental health challenges. In an effort to reclaim harmful language, this article includes mad as a term of empowerment for those who have been excluded socially and/or pathologized by the clinicians, hospitals and rehab centres that have “treated” them. The title “Mad in Islam”, then, refers to Muslims and their allies who recognize the need for programs and services established by Muslim communities for mad Muslims.

The surah Al-Ma’idah (the table spread) – a chapter of the Qur’an – states: “Satan only wants to cause between you animosity and hatred through intoxicants and gambling and to avert you from the remembrance of Allah and from prayer. So will you not desist?” (5.91) Intoxicants, but in particular alcohol, create a spiritual barrier between God and the believer. While scripture does not provide much explanation as to what establishes this barrier, the dulling properties of alcohol are a detriment to prescribed activities, like salaat – prayer – or iqraa – the study of scripture –, that require alertness and authentic intention.

Dr. Shaheen Azmi, a leader in the North York Islamic community and social sciences scholar who has written on Muslim communities in Canada, explains that Islamic scholars have examined in detail the impact of intoxicant use on human life and various conclusions about it have been established. It’s safe to say that a unanimous decision has been made about the overall notion that alcohol has a “destructive power”.

Alcoholism is less problematic in Muslim societies because it is socially unaccepted in all contexts, explains Dr. Azmi. On the other hand, the stigma attached to alcohol consumption also results in a “limiting recognition and response to alcoholism in these societies and cultures.” What makes alcohol consumption different from other prohibited activities in Islam is that some people, Muslim or not, are predisposed to alcoholism. Due to a series of genetic, environmental and social factors, there are Muslims who unwittingly become trapped in a cycle of alcoholic self-medication.

Samira Kanji, president of the Noor Cultural Centre in Toronto, says that she is aware that alcoholism exists in her community. In regards to mental health issues in general, she writes, “[it] is no more shameful than any other corporeal illness, being as much a part of God’s endowment.” As a response to mental distress in her community, Sr. Kanji suggests that Muslims should recognize the “frailties” and “limitations” of the human spirit, as “our tests in this life include how we deal with our own (with gratitude and patience), and also how we respond to those of others (with kindness and empathy).”

For legal, social and religious reasons, alcoholism in Islam is shrouded in secrecy. In predominantly Muslim countries and in countries where alcohol is outright banned, there is regardless a continuing need for drug and alcohol treatment programs. For instance, while alcohol is prohibited in Iran, a country primarily regulated by Islamic law, there are dozens of Alcoholics Anonymous or “AA” groups that provide support to the local alcoholics. Being Muslim and being addicted are compatible even in those countries where alcohol is banned. In fact, the infamous form of contraband alcohol colourfully termed aragh sagi, literally dog sweat, is popular among Iranians.

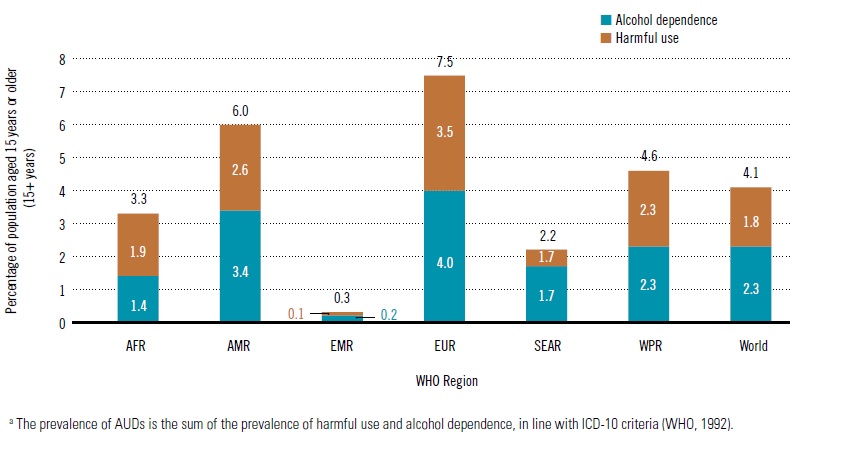

The World Health Organization’s 2014 report on alcohol and health states that in 2012 5.9% of global death was attributed to alcohol consumption. The WHO reports on alcohol related death per region. Unsurprisingly, the region with a predominantly Muslim population reports that alcohol abuse impacts less than 1% of the population. However, the WHO forewarns that about 50% of alcohol use in predominantly Muslim regions, which the report refers to as the “Eastern Mediterranean region” (EMR), is unreported and up to 100% of it is unreported in Muslim countries where it is banned. That being said, black-market alcohol is a reality in predominantly Muslim countries. Kuwait, Afghanistan, Iran and Yemen have a history of illegal alcohol consumption. Muslims countries, like Pakistan, only sell alcohol to non-Muslim minorities.

Alcohol Abuse and Dependence by WHO Region (see EMR/Eastern Mediterranean Region)

Addiction can impact anyone regardless of race, gender, religion, class and creed. While access to alcohol increases in countries where it is openly sold and regulated, that there are AA meetings and the presence of black-market alcohol in countries where it is outright banned speaks to the large percentage of unreported alcohol use in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR).

Aziz and Ahmad

Ahmad*, a thirty-something Muslim man who recently attended an established alcohol, drug and gambling rehab centre in Ontario, wishes he had access to “Muslim counselors or doctors” who could understand and validate his internal conflict toward drinking. He felt alone during his stint in rehab. If there were any other Muslims in his treatment group, they were not willing to talk openly about their addiction to alcohol.

Sober for over a year, Ahmad now recognizes that he was self-medicating with alcohol. The depression began in his adolescent years, but madness was never a topic of discussion in his family. The alcohol was an easy answer to a difficult problem – or so he thought.

Aziz, like Ahmad, is a Toronto-based Muslim alcoholic in recovery. The son of devout Muslim immigrants, he learned from a young age that alcohol is haram. Aziz had his first drink when he was twenty-five years old. Pressured by his non-Muslim girlfriend at the time, he thought it would be fun to try once, knowing that any amount, whether great or small, is haram.

Recreational use does not usually lead to addiction, but both men weren’t aware of their own alcoholic tendencies. After all, they couldn’t consider factors of family history. What they did know is that after their first drink, they simply could not stop.

When Aziz began to look for support, he found Alcoholics Anonymous, but was quickly turned off by its “white Anglo-Saxon Protestant” overtones. Like Ahmad, Aziz didn’t feel like people understood why it was so difficult for him to be open about his alcoholism and why it was equally difficult for him to accept the fact that he had a drinking problem. After some prodding, Aziz admitted that It wasn’t the “whiteness” of AA that bothered him, it was the fact that he “couldn’t fully relate to any alcoholic” he would come across during his recovery.

For Aziz and Ahmad, it was a well-founded fear of ostracization that made their situations unique. They had similar experiences – conventional Western medicine helped them get clean, but they found that recovery based support, which encourages consumer independence, was lacking in their own communities. When Ahmad was asked about the possible repercussions of him revealing to his family his addiction, he said, “My mother and father would disown me. This is something I could never talk about.” He added, “If I did tell my parents, the rumours would spread like wildfire and everyone [in the community] would find out. I wouldn’t be able to show my face for jummah [congregational prayer] again.”

For those in Ahmad’s environment, alcoholism is the result of moral defect. Alcohol consumption of any kind is grounds for social exclusion in some – if not most – communities. This creates a striking contrast in regions where casual consumption of alcohol is socially acceptable and even encouraged. For instance, to dine at a restaurant where alcohol is served, explains Aziz, is frowned upon in his social circles. In fact, the use of vanilla extract in baking is, for some Muslims, equally haram.

Muslims like Aziz and Ahmad are driven to double lives because of the understanding that alcohol consumption is an act deserving of punishment (Islamic law goes as far to say that the drinker must endure a certain amount of “lashes”, explains Dr. Azmi). While the young Muslim men are not worried about lashings, they are afraid of losing their families and friends. It’s hard to say which of the two outcomes would be more painful.

Final thoughts

Recovery model addictions medicine specialists, peer support groups, drug and alcohol rehab centres, detox centres and self-help groups are all possible components of the mad Muslim’s journey. In an ideal world, some of these services would cater specifically to the Muslim demographic. These services could, for example, encourage the alcoholic to participate in salaat, wudu (ritual cleansing) and, when physical health permits, ritual fast. Aziz and Ahmad hope to one day have access to therapy and psychoeducational groups “run by Muslims for Muslims” to ultimately include their families as supports in their recovery and to learn together about addiction and the brain. To “be accepted for who I am – first as a human being, then a Muslim man and lastly, an alcoholic in recovery”, is what Ahmad wants for his future.

The Muslim alcoholic is a rare bird, this is certain, but one that might not appear to be so unattainable if mad Muslims and allies took a moment to listen. This might appear to be a daunting task, but we must be fearless in the face of change. So, as Rumi wrote, be “the fearless rose that grows amidst the freezing wind” and speak against the stigma of addiction in your community.

*Names changed to protect identity

Want to learn more check out the Public Radio International story from December 12, 2012

Muslim alcoholics try to bring hidden problem into mainstream

http://www.pri.org/stories/2012-12-12/muslim-alcoholics-try-bring-hidden-problem-mainstream

| Many thanks to Ariane Bakhtiar for opening a conversation about Compassion, Madness, Addiction and Islam. Compassion is more important than our different approaches to religion, medicine and Mad Studies. Compassion is at the root of living together with our Madness. |